Voices and the brain

Understanding the brain mechanisms involved in voice-hearing can help us get a better grip on why it is that voices occur and how they might be linked to inner speech, memory and previous life experiences.

What’s happening in the brain when someone hears voices?

One technique that neuroscientists often use to answer this question is . This allows them to track where blood flows around the brain, and therefore which bits are busy processing information.

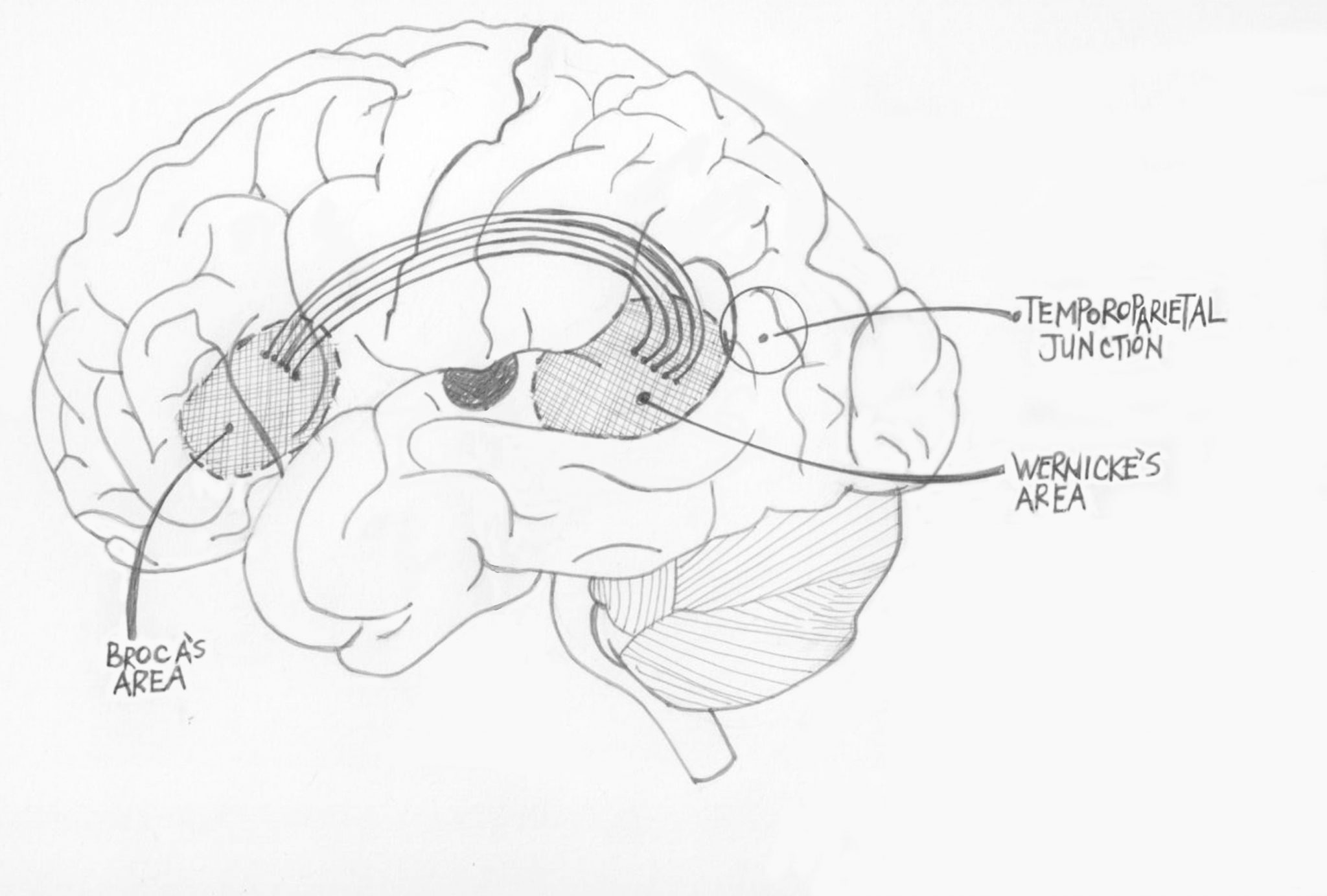

fMRI studies reveal that a few specific areas of the brain seem to be more active than others when someone is hearing a voice. One of these is , situated near the bottom of the frontal lobe, and which plays an important role when we are speaking out loud. Scientists also know that Broca’s area is involved in talking to yourself in your head. That is, it is important in producing inner speech.

Another area that seems to be active when someone hears a voice is at the top and back of the temporal lobe (on the side of the brain). This brain area is important in understanding speech , and also in having a feeling of control over our actions (the ). Interestingly, there is some evidence that the connections between this region and Broca’s area are different in people who hear voices. This might also suggest links between voice-hearing and inner speech.

Image provided by Mary Robson.

Voices and prediction

Recently researchers have become interested in the idea of the brain as a ‘prediction machine’, whose main job is not to process information coming from outside, but instead to predict what is happening in the world and adjust those predictions on the basis of new information. The theory holds that, when we perceive the world around us, there is often too much to take in, so our brains take shortcuts or ‘fill in the gaps’ based on past experiences and what we have learned to expect about our environment. This process is known as .

Some researchers have applied the notion of predictive processing to hearing voices. According to one theory, we make mistakes in perception when we are stressed, tired or under threat. Imagine, then, that over time your brain get used to there being particular threats in the world: snide comments, whispers, or outright abuse. If you have long periods of sleeplessness, problems with drugs, or big changes in your life that are making you feel stressed, your brains might start interpreting incoming sensory information (‘filling in the gaps’) in terms of what it has learned about the world. In some cases, this could give rise to experiences of unpleasant voices; in other cases, it could result in seeing a dark shadow, or feeling like someone is touching you or pushing you.

You can find out more about what’s happening in the brain when someone hears voices and predictive processing accounts of voice-hearing by watching the hollow mask illusion video.

The hollow mask illusion provides a good example of predictive processing in action. We know from past experience that human faces are always convex (i.e. curved outwards). As a result, our brains take a short cut – ignoring things like shading and shadows – and we perceive the hollow side of the mask as a normal convex face.