Voices in medieval mysticism

In the Middle Ages, the existence of heaven, hell and a spirit world were taken for granted; anyone might encounter God, the Devil, angels, demons or ghosts. Some people actively pursued a direct connection with the divine, seeking visions – often involving more than one of the senses – as a means of increasing religious knowledge. Voices were often an important part of these visionary experiences.

In this section, we look at two women whose visionary experiences were written down in texts which continue to inspire Christians and fascinate historians today. If you would like to learn more about visionary experiences in the medieval period more broadly, you can listen to the podcast below.

Margery Kempe

One of the most influential records of voices and visions within the Christian tradition is The Book of Margery Kempe. Margery, who was

Margery’s visions often involve more than one of the senses, and voices play a prominent role. The

The Book is shaped by Margery’s conversations with the Lord, often described as visitations while she is praying or contemplating, and by experiences in which she sees not only with her ‘ghostly’ but also her ‘bodily’ eye. In her visions, Margery enters into a dramatic spiritual world where she takes part in Biblical history – assisting at Christ’s

Margery’s extreme emotional responses and displays of loud wailing, writhing and weeping were often treated with scepticism by both

Part of Margery Kempe’s significance today lies in the richly autobiographical nature of her book. She provides us not just with a spiritual and social commentary, but also with one of the most powerful insights we have into the experience of ordinary women in the Middle Ages.

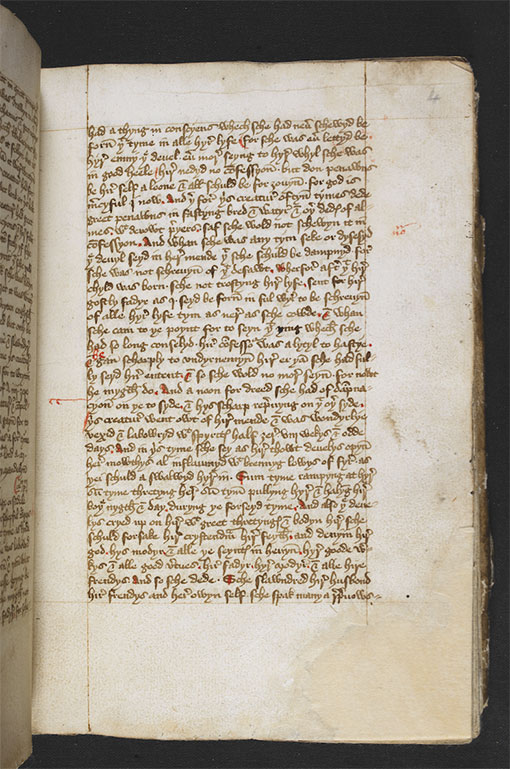

The Book of Margery Kempe (above) records the mystical experiences of Margery Kempe. This page describes devils “pulling her and hauling her about both day and night”.

©The British Library Board, Add MS 61823, f.4r.

Julian of Norwich

Margery Kempe visits St Julian of Norwich

An icon by Brother Leon of Walsingham, depicting Margery Kempe’s visit to Julian of Norwich.

Image credit: St Michael and All Angels Church, Brighton.

Julian of Norwich was an English mystic, who lived much of her life in permanent seclusion. Little is known for certain about her actual name, her family, or of her life before she became an anchorite.

An anchorite was someone who was walled into a cell to live a life of prayer and contemplation. Julian lived in a cell attached to St Julian’s Church in Norwich.

In 1373, aged just over 30 and suffering a

Many of Julian’s experiences have a conversational quality to them. For example, in one passage, God shows Julian a hazelnut. The nut is revealed to her as an image of creation – ‘all that is made’. She asks:

What can this be? I was amazed that it could last, for I thought that because of its littleness it would suddenly have fallen into nothing. And I was answered in my understanding: It lasts and always will, because God loves it; and thus everything has being through the love of God.

In a similar way, Julian receives answers to some of the deep questions with which she is struggling – as when she cannot understand why God allowed sin in the world. ‘Jesus … answered with these words and said, Sin is necessary, but all will be well, and all will be well, and every kind of thing will be well.’

Around 1415, Julian was visited by Margery Kempe, who had been prompted by one of her voices to come to Julian’s cell and ask for her authoritative help in interpreting and validating her own mystical experiences. We don’t know exactly what the women discussed or what they made of each other, but, in Margery’s words, ‘Great was the holy conversation that the anchoress and this creature had through talking of the love of our Lord Jesus Christ for the many days that they were together.’

Find out more

Read

Chris Cook (2018). Hearing Voices, Demonic and Divine: Scientific and Theological Perspectives. London: Routledge.

Corinne Saunders (2015). Hearing Medieval Voices. The Lancet.

Listen

Otherworldly Encounters: Voices and Visions in the Medieval Period – A recorded lecture by Corinne Saunders, produced by Andrea Rangecroft for Hearing the Voice.

Hearing Voices in the Christian Mystical Tradition – A recorded lecture by Chris Cook, produced by Hearing the Voice.

Watch

Charles Fernyhough (2018). Living with gods: Inner voices. The British Museum.

Explore

Visionary Voices – A podcast exploring voice-hearing and divine inspiration, including interviews with Corinne Saunders, Chris Cook and Hilary Powell.

Otherworldly Encounters: Voices and Visions in the Medieval Period – A recorded lecture by Corinne Saunders, produced by Andrea Rangecroft for Hearing the Voice.

Hearing Voices in the Christian Mystical Tradition – A recorded lecture by Chris Cook, produced by Hearing the Voice.

Visionary Voices – An online exhibition exploring the spiritual aspects of voice-hearing in the medieval period. Part of Hearing Voices: Suffering, inspiration and the Everyday.