Emily

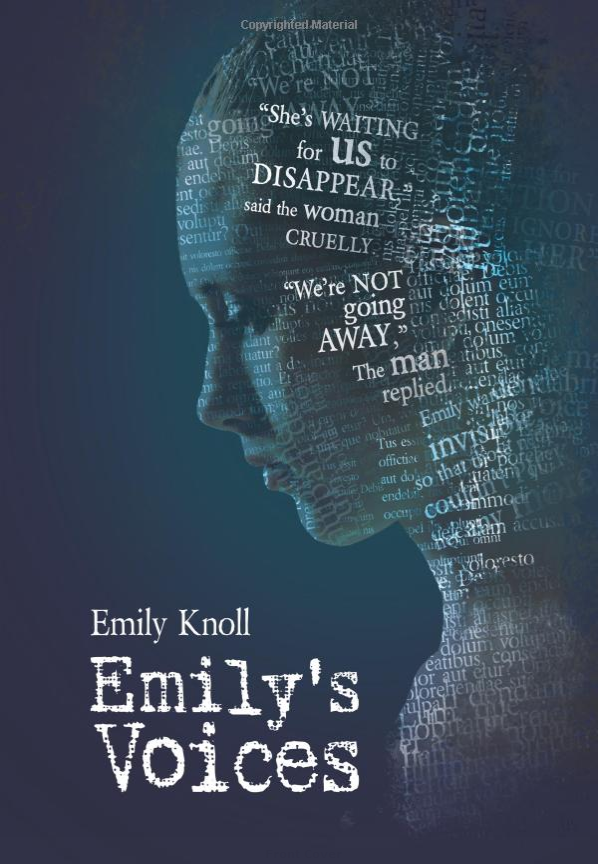

Emily Knoll is a writer and researcher who hears voices. She has written a fictionalized memoir, Emily’s Voices, about her struggle with her experiences and journey through the mental health system. You can purchase Emily’s Voices on Amazon here and read two extracts from the book below.

Please tell us about this piece of work. How is it linked to your experience of hearing voices?

I felt that I had been stigmatized by some mental health professionals, who gave me very low expectations of recovery, and told me that I could expect to be long-term unemployed, as I was ‘disabled’. I was advised to go on benefits, and to accept that I was ‘ill’. So, when I did eventually find a job, and then found that I got stigmatized in that job, I turned to my writing to try to make sense of what had happened to me. Eventually I was able to find a therapist who encouraged me to accept the voices, to live with them, to live alongside them. This therapist encouraged me to write Emily’s Voices, and to enrol on a Master’s course.

How (if at all) does making art help you cope with or explore your voices?

My writing helps me makes sense of what has happened to me. I found it a healing process to reflect in my book Emily’s Voices on the people and places that had hindered me, and those that had helped me to recover.

I also write in my diary about my voices. I was asked by a professor from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, who had teamed up with my research team, to record my inner experience for a study that he was doing. I found the process challenging, as an entry from my Reflective Journal shows:

5 October

I’m glad that I’ve taken part in Russ’s ‘hearing voices’ study, as it has made me think about the connection between my thoughts and what voices I hear. They do appear to be linked in thematic content. I found it difficult to talk about how the voices have physical presences, which are external to me, as if they are people. This, of course, is a delusion, so it needs to be deconstructed which them makes it an ‘illusion’.

Reflecting on what was happening for me enabled me to start to understand my voices more. What had once been a bewildering, frightening phenomenon was now becoming fascinating on an intellectual level. Through diary writing, I was gaining more insight as I stepped back from the experience to examine it. Creative practices like these offer a space that I can use to mediate a different relationship with my voices.

What role do your voices play in the creative process? Do they inspire you or do they sometimes ‘get in the way’?

I don’t find that my voices inspire me, but I do know other voice-hearers whose voices help them to write poetry and works of fiction.

What’s your advice to other voice-hearers thinking of using creative activities as a means of coping with or exploring their experiences?

I would suggest using a range of creative practices when attempting to cope with challenging voices. As I describe in my book, I often play the cello when I feel distressed. When I listen to myself playing pieces like ‘The Swan’ the voices don’t intrude too much. I tell myself that the voices are just another noise. Diary writing is also helpful.

Gloria now gave me so many chores that I had no time to leave the flat until late in the evening. I would try to stay calm, but when I finally got out of the flat I’d be furious, as usually I’d be late to meet my friends. This left two hours, at the most, to chat with my friends over a glass of wine before I had to leave. I needed to be awake and out of bed early in the morning to get the oldest boy up for school.

My friends Beth and Sarah I had known since sixth form, and both were living and working in London. But often I couldn’t relax, because even with them I’d sometimes hear the men’s voices, or the spiteful female voice. I was convinced I’d lose them as friends if they knew. So I took care to hide how frightened I felt at the voices. Inevitably, I looked tense and preoccupied as I struggled to cope. I even took to drinking wine in an effort to calm myself. One evening on the way home I bought a bottle of whiskey and sneaked it into the flat in my bag; I hid it in my wardrobe, and locked the door. I told myself that if I really couldn’t sleep, I would drink a glass of whiskey, as I didn’t want to go to the doctor to get sleeping pills.

I felt relief when the cooking seemed to go better for a while. I needed to feel a sense of control over what I was doing. I knew that much about myself.

But I couldn’t escape the voices. I retreated to the nearby café to read, whenever I could, but this was futile.

“I thought she wouldn’t come out,” shouted the brittle male voice. His tone was nasty.

“Maybe she needs to find out,” shouted an older male voice.

Find out what? I looked up at the window to see a young woman passing. So where were they? There was more shouting, as the cars sped past. Were the woman and the men further down the street, out of sight? I felt oddly disorientated.

I had to go and see for myself what these voices behind the wall really were. I grabbed my coat. It was chilly outside. Cars were passing, and as they rushed past me the voices became louder. I could still hear each voice separately – and as more cars passed, they became a deafening roar.

“She fancies herself,” said the female voice spitefully.

“Is that it?” shouted the older male voice.

“We’re looking at her now,” roared the brittle male voice.

This made me very afraid again. These people were talking about me. I didn’t like that. So I walked up the crowded street to search for the voices, but I didn’t find them. Then I turned down a quiet side street. I could still hear the voices. Were the woman and men on the corner of the road? I wanted to shout out, who are you? But what if these were ordinary voices? People might think I’m crazy.

Emily’s Voices, Chapter 7, pp. 66–68

One of the mental health workers at the day-centre had found about a ‘hearing voices’ training course being held at Camden Mind in London, for people who were hoping to facilitate peer support groups for voice-hearers. She suggested to me that we attend this together. I was so miserable trying to cope with the voices on my own that I agreed. The course was held on the fourth floor of a grey office block with large windows. Rai was the course facilitator – and also a voice-hearer; she was warm and chatty, in her bright red jumper and jeans.

“Could you tell the person you’re sitting next to where you would visit if you could go anywhere?” asked Rai.

I froze. This was the kind of ice-breaker activity that I used to give students when I was a teacher. I didn’t like being the person doing the activity.

I turned to the smiling Chinese woman next to me. “Home – Beijing,” she said. “Where would you go?”

“Venice,” I replied. My voice was shaking, as it was three years since I’d had a holiday, I couldn’t now imagine going abroad, still hearing voices. In an aeroplane you’ve closed into a tiny capsule: what if I shouted back at the voices?

So I was very surprised to find out that morning that Rai had recently flown back from a mental health conference in New York. She was hearing over ten different voices, nearly all of the time. They even had names that she’d given them, like ‘the Scream’. Some of the voices she hated, as they made her afraid and anxious; other voices she welcomed, as she had made friends with them. The thought of inviting in my own voices filled me with alarm. So when Rai asked people to volunteer their own lived experience that afternoon, I was reluctant to put up my hand. I was reluctant to put up my hand, I didn’t want to share anything about the voices, as they felt so personal to my experience.

“Yes, you can live with voices,” Rai said to the group. “That’s how you guys are going to help each other, as you’ll be giving voice-hearers a safe space where you can talk about your voices in groups, and support each other.”

My hand shot up. “Could you tell us some coping strategies for dealing with voices? My voices are really nasty to me.”

Rai smiled, and said, “I’ve got a hand-out with coping strategies on it. And I’m going to run through a couple of strategies that I’ve found really helpful, like writing down what the voices say in cartoon bubbles, and talking back to the voices.”

I stared at her. I hadn’t even dared to engage with my voices by having a dialogue with them. I had only ever told them to shut up!

Emily’s Voices, Chapter 11, pp. 106–108